The ACIP (Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices), a branch of the CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention), recently changed its recommendation for universal administration of the Hepatitis-B vaccine to newborn infants before they leave the hospital. Let’s unpack this recommendation and its consequences.

The AAP (American Academy of Pediatrics) continues to recommend routine delivery of the first Hep-B vaccine within 24 hours after birth. The second and third doses in the series are due at two months and six months of age. Regarding Hep-B vaccination, the AAP released this statement: “The pacing of these doses has been rigorously tested and proven to be safe and effective over several decades. Delaying the birth dose of the Hepatitis-B vaccine has no clear benefits and leaves children vulnerable to infection.” Indeed, newborns who contract Hepatitis-B have a very high likelihood of developing chronic, and possibly fatal, liver disease.

The most common routes of transmission for Hepatitis-B include sexual contact (unprotected sex with an infected individual), blood contact (sharing needles for drug use or tattoo or piercing equipment), contaminated personal grooming items (razors, toothbrushes, nail clippers, or pierced jewelry with microscopic traces of infected blood), and vertical transmission (during childbirth from an infected mother to her baby).

Up to 90% of babies infected with Hepatitis-B will go on to develop chronic, lifelong disease, including liver damage, cirrhosis, liver cancer, liver failure, and potentially death. Nearly 25% of children with chronic Hepatitis-B will die from liver disease. Vaccination within a day of birth, or delivery of passive Hep-B immune globulin to babies born to infected mothers, can halt this progression. If infected, newborns may demonstrate jaundice, fatigue, abdominal pain, or dark urine. But many affected babies will show no symptoms at all, which can delay diagnosis and put those patients at high risk for serious chronic disease and death.

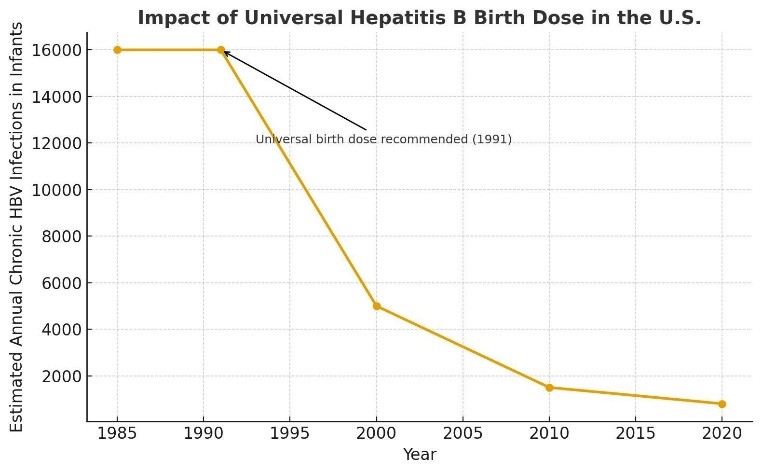

When it was introduced in 1991, universal newborn vaccination with Hepatitis-B demonstrated a shockingly impressive effect— new infections in children and teens plummeted over 95%, cases of chronic Hepatitis in children fell from about 16,000 cases per year to under 1,000, and Hep-B-associated liver cancer in children became a rarity. Fewer youngsters infected with Hepatitis-B translates into fewer adults with the disease, and that means fewer infections handed down from generation to generation.

Hepatitis status is part of the standard battery of pre-natal testing, but some mothers become infected in-between the time of testing and the baby’s delivery. That means that reserving the Hepatitis-B vaccine for only known cases at risk for vertical transmission will necessarily miss a sliver of the population. So while it might provide more coverage than what is absolutely necessary, the birth dose of the Hepatitis-B vaccine provides immediate protection to the most vulnerable population, and acts as a vital safety net against transmission from mothers during childbirth and accidental exposure from other contacts soon after birth. This approach has already demonstrated remarkable success globally after its initial introduction, preventing long-term morbidity and mortality across generations.